In spearfishing, the action happens fast.

I’m swimming next to Chapman Ducote at a spot known as Silver Hole in the Bahamas’ Cay Sal Bank. His dive buddies, Ian Miller and Rodrigo Franco, fan out around us. The water’s deep and the visibility isn’t as good as anticipated—I can see clearly for maybe 20 feet, but the ocean floor is another 20 below that, and then the blue hole drops an unfathomable hundreds, maybe thousands, of feet towards the center of the earth. The water has an eerie, shadowy quality.

When Ducote dives down, I dive too, practicing what he’s taught me about prepping my breath, progressively clearing my ears, tucking my chin for a straight-down approach and counting my kicks. The ocean reveals itself in layers. I spy the seafloor with its sandy bottom and patchwork of coral heads along the abyss of the blue hole. Streams of light refract through the cloudy water from where the bottom falls out. Maybe I’m 30 feet deep. I hang for a moment and watch Ducote continue his free dive into the hole on one breath, his nine-foot Riffe pole spear in one hand. He looks like the tiny toy diver inside a kid’s aquarium, or perhaps, more like Aqua Man. I make my dolphin kick up to the surface.

A large school of snapper with brilliant yellow tails unfold past us like a wave and Miller gestures me towards him to get a closer look. I don’t remember if it was the subtle, yet inexplicable, whistling sound of a spear fired under water or the shock of the fish dispersing in every direction that signaled to me someone hit a fish. I look and see that Franco has one wriggling at the end of his spear.

In an instant, the bull sharks are on us.

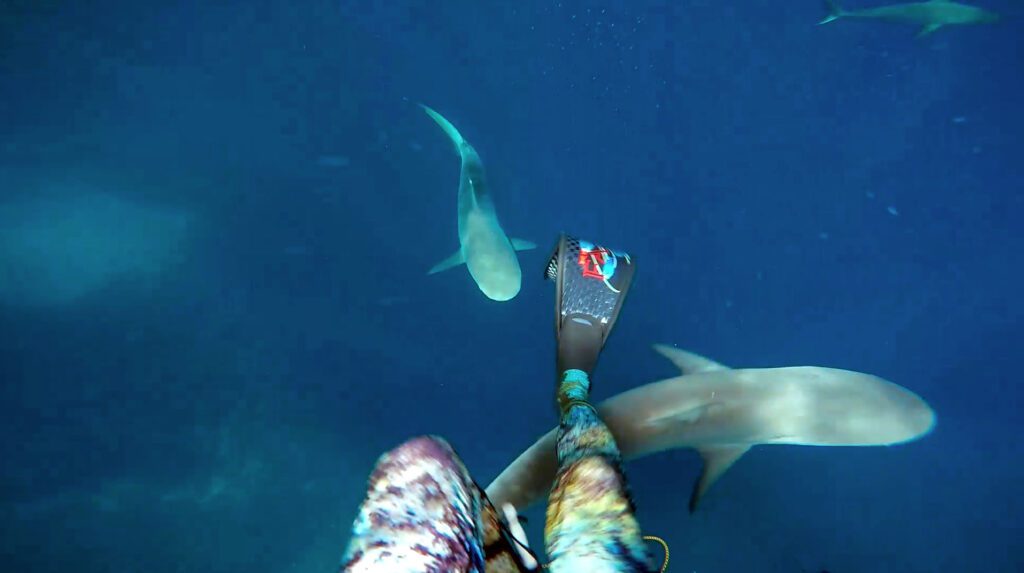

Three of them, big—maybe seven or eight feet long—fast and darting at Franco, repeatedly, like underwater torpedoes. I hang back with Miller, maneuvering myself around him, trying to keep my distance and stay calm, repeating, “Okay, okay, okay” through my snorkel, like a mantra.

Ducote swims into the fray as Franco forfeits his fish. One of the sharks circles back aggressively at Franco’s feet and he kicks at it repeatedly with his long fins as another shark buzzes his side. On the shark’s next approach, Ducote is there with his spear and hits it square in the nose, bending his pole. I peer above the water and blessedly, the boat is right there. We swim towards it and hoist ourselves onto the teak platform of Ducote’s Delta 54, unscathed and out of harm’s way.

“Is that enough excitement for you?” Ducote howls, tossing his mask and snorkel onto the platform, his bright smile beaming against his green pixelated camouflage wetsuit.

We’re filled with adrenaline and nervous laughter, vibrating somewhere on the spectrum of shock and exhilaration. “For a second there, I seriously thought I was going to get bit,” Ducote says, surveying his gear to discover a chafe mark the length of a tooth on the line connecting his spear tip.

These brushes with sharks don’t faze Ducote and his friends, all experienced spear fishermen and free divers who set off to the Bahamas from Miami every chance they get. And this wasn’t the first or last encounter we’d have with sharks on our three-day journey through Cay Sal Bank, a largely uncharted area of 46-square-nautical miles in the southern Bahamas, just 10 miles north of Cuba. The sport involves diving to depths of over 100 feet of water on one breath of air with nothing more than a mask, snorkel, weight belt and spear in hand. Most of our dives on this trip are in 30 to 60 feet of water and the guys stay under for an average of about a minute each dive, no sweat. They’re on the hunt for fish we can eat for dinner. In these waters that means, blackfin tuna, grouper, wahoo, mackerel, permit, hogfish, snapper, mahi-mahi, African pompano and yellow jack, to name a few.

When I ask Ducote if he has any interest in the more traditional form of fishing with a rod and reel, trolling from the back of the boat, his response is emphatic: “No. Not at all. We don’t even have fishing poles on the boat,” he laughs. “There’s too much waiting around and it’s not athletic enough. You’re just sitting on the back of the boat drinking beer, waiting for something to happen. I don’t have the patience for that.” For these guys, it’s all about the thrill of the hunt and testing their limits in the fish’s natural habitat, not to mention the otherworldly beauty of being under the sea. As Franco advised me on an early dive, “Become one with the ocean.”

Ducote and his interests are as high-octane as the $2.3 million, state-of-the-art Delta 54 Swedish yacht that we’re cutting through swimming-pool-blue Bahamian waters aboard. A decorated professional racecar driver and successful entrepreneur based in Miami, Ducote’s preferred speed is fast. The New Orleans native has been on the water as long he can remember, commanding his own nine-foot Zodiac at age four, and today at 39, as Delta Carbon Yachts first North American distributor, he’s like a kid in a candy store. “I always wanted to be in the boating industry, but I didn’t think I’d be there by 40,” he tells me from the helm.

“Delta’s the first large production boating company to really take advantage of [carbon fiber’s] hydrodynamic potential.”

Chapman Ducote, North American distributor of Delta Carbon Yachts

With smart design, cutting edge technology and sleek lines that are at once modern and vintage, Ducote loves the boat’s versatility, “You can dress her up and take her to the club or go hard core.” But it’s the carbon fiber technology that initially drew him to Delta, and he brought Miller on board as his VP. “Carbon fiber saved my life,” he says of the ultra lightweight and super durable material, recalling his racecar driving days. “Delta’s the first large production boating company to really take advantage of its’ hydrodynamic potential.”

We’ve made our way to the western stretches of the bank and anchor near uninhabited Cay Sal Island just before sunset. The coolers are full of yellow jack, grouper, a giant permit and more spiny lobster and conch than we can count all caught that afternoon. The sunsets in Cay Sal are brilliant, glowing in Technicolor, reflecting on the ocean’s surface. I see the fabled green flash—the denouement of the sun’s disappearance beyond the horizon as an instantaneous neon spark—for the first time in my life.

We begin our nightly ritual of prepping dinner. The guys clean the fish while I chop vegetables and squeeze fresh lemon and lime juice for conch salad and yellow jack crudo. Lobster tails and permit filets are slathered with butter and flame grilled with brussel sprouts and shishito peppers. Food just doesn’t get any fresher than this.

After dinner, we climb to the cushions on the bow and gaze at the night sky. Free of light pollution, the stars are suspended in breathtaking 3-D with the Milky Way’s band of stardust clearly visible and shooting stars crossing the bow. The only hint of civilization is a subtle glow on the southern horizon, the lights of Havana.

“We’ve gotta stay another night,” says Ducote in the morning with his signature devil-may-care swagger. He’s standing on the roof of the Delta 54, profiling the uncharted waters, looking for coral heads and ledges that attract fish. “You just don’t get days like this.” The boat’s cruising atop 80-foot deep crystal clear water and we can see straight to the bottom. Compared to the confused seas and wind chop yesterday at the blue holes, it’s flat calm now with the otherworldly rocks of Elbow Cay protruding from the water on our starboard side like a never-ending spine. We’re the only boat in sight.

The current’s ripping and we stop to drift dive in 60 feet of water for about a mile. It’s a dreamlike experience, floating with the current and observing the world below: a giant stingray flutters along the ocean floor, a nurse shark snoozes by a patch of sea grass, a juvenile loggerhead sea turtle swims to the surface. The water is brimming with lobster and the guys add to our bounty.

The Gulf Stream is with us on the three-hour journey back to Miami, kicking our cruising speed up to 38 knots. After three full days in the water, the guys average about 100 dives each and the boat will have traversed close to 400 nautical miles. Franco holds the depth record at 95 feet going after a giant lobster inside Shark Hole, and also the duration record at over four and a half minutes on one breath on a shallow dive hunting lobster inside a coral cave.

We come across a weed line—an accumulation of seaweed floating on the surface in a long, thick line, shaped by the currents, where pelagic fish are often found feeding—and the guys hop in the deep, velvety water with their spears. “This is where we see tiger sharks,” Miller warns me. I hang back on the deck and watch. They’re on the hunt for mahi-mahi and giant tuna. In five minutes, they spear five mahi, holding the electric yellow-green speckled, blunt-nosed fish overhead at the end of their spears before tossing them onto the platform and into the cooler.

We’ve only been underway for a few miles when someone spots a pod of Atlantic bottlenose dolphins. This time, I squeeze into my fins, grab my mask and snorkel and jump in with the guys—tiger sharks be damned. We swim a full crawl towards the pod and get close enough to dive under water and swim alongside them for a few feet. We come up for air as the dolphins swim away, but our timing is perfect for the sunset. We tread water, the open ocean plunging thousands of feet below us, and watch.

Another green flash.

We holler and slap the water’s surface, flapping around like giant fish, ourselves.

On bow watch, under the dark night’s sky with the Florida Keys glimmering to our port side, Miller mentions that the three bull sharks back at Silver Hole rank in his top three shark encounters.

“Seriously?” I ask. “What’s one and two?”

“Coming face to face with a nine foot tiger shark,” he tells me. “And the time I shot a fish and two bulls went for it at the same time, smacking into each other at full speed right in front of me.”

Laying on my belly on the bow with a sharp headwind in my face, I can’t decide if I’m freaked out, or if I suspect that I’m one of them. I’ve joined the tribe of divers who are cool and unafraid in the face of a menacing shark. It wasn’t that scary, I tell myself. The truth is, swimming in the deep open ocean with sharks lurking in the shadows is both terrifying and awesome.

A version of this story was originally published in BOAT International.